Subtropical storms in the Atlantic Basin can occur one or more times each hurricane season and are a mix of two different, familiar storm types.

To explain subtropical storms, we need to start by explaining these two different storm types with which subtropical storms share some characteristics.

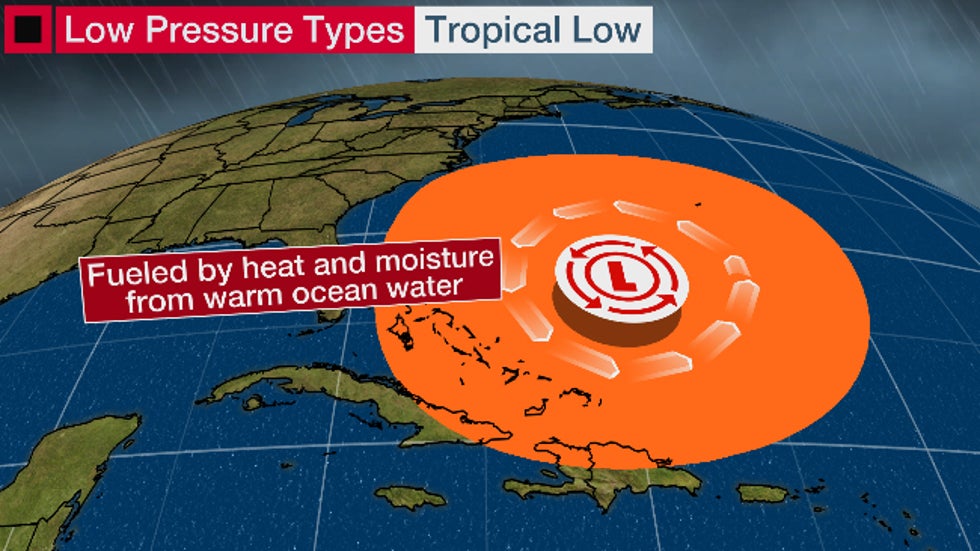

Type 1: Tropical Storms: Tropical storms, or more broadly, tropical cyclones, are low-pressure systems fueled solely by heat energy released when water vapor evaporated off warm ocean water condenses into liquid. Due to all this heat, the core circulation of a tropical cyclone is warm and its strongest winds are usually found near its center.

With low wind shear and moist air, these tropical storms can intensify into hurricanes. The National Hurricane Center issues forecasts for each of these tropical cyclones once they become at least tropical depressions.

Type 2: Extratropical Lows: An extratropical or non-tropical low, however, derives its energy from contrasts between cold and warm air.

They always have at least one front – cold, warm or occluded – attached to them. You can see several examples in the current weather map below.

They can occur both over the ocean and over land, and are responsible for most of the precipitation that falls over land areas in the middle latitudes. They take the shape of winter storms, powerful storms marching in from the Pacific Ocean, coastal storms along the East Coast, or even just a low driving a strong cold front out of Canada with relatively little precipitation.

An extratropical storm’s core is cold, and its strongest winds are typically quite far from its center.

The strange brew of a subtropical storm: An interesting thing happens when an extratropical or non-tropical low begins to warm up.

This can happen when the low slows down, tracks over ocean water just warm enough – usually at least 70 degrees Fahrenheit – and thunderstorms begin to percolate closer to the low-pressure center.

If winds aloft aren’t too strong to blow away the low-pressure center but instead help ventilate the storm, encouraging rising air and thunderstorms, the core of the low-pressure circulation will warm, first in the lower levels.

At that point, this system becomes a subtropical cyclone, exhibiting features of both tropical and non-tropical systems.

It’s now deriving some of its energy from warmer ocean water, like a tropical storm, but also some energy from the lingering temperature contrast that originally spawned it as an extratropical storm.

Subtropical cyclones are typically associated with upper-level lows and have colder temperatures aloft, whereas tropical cyclones are completely warm-core and upper-level high-pressure systems overhead help facilitate their intensification.

Why subtropical storms matter: The NHC issues advisories and forecasts for subtropical depressions and storms. They are assigned a number or name, just like a tropical depression or storm.

Strictly speaking, subtropical storms cannot directly intensify into hurricanes. But there is a path to doing so.

If the subtropical storm remains over warm water, thunderstorms can build close enough to the center of circulation, and latent heat given off from the thunderstorms can warm the air enough to create a fully tropical storm.

Once that happens, further intensification into a hurricane becomes possible.

Even if they don’t eventually become tropical storms or hurricanes, they can still produce soaking rain, strong winds and rough surf.

Mature subtropical cyclones often have a large, cloud-free center with thunderstorms and rainbands displaced some distance away.

Maximum sustained winds are also much farther from the center, while the strongest winds in a tropical storm are close to the center.

Subtropical storms can also generate swells that can reach the coast, producing high surf and rip currents.

Visible satellite image of Subtropical Storm Andrea off the east coast of Florida on May 9, 2007.

Here’s how often they happen and some recent examples: Subtropical storms were not officially recognized until the beginning of the satellite era, and they weren’t named until 2002.

They don’t occur every hurricane season. When they do, it’s typically early or late in the season, when colder upper-level lows and former extratropical lows in more southern latitudes are more common.

After review, the NHC found that a subtropical storm formed in mid-January 2023 off the Eastern Seaboard. Since it wasn’t designated as such at the time, it will remain unnamed. The storm eventually moved into Nova Scotia, Canada, but there were no reports of damage or casualties.

Six months later, Don sprung to life over the North Atlantic as a subtropical storm on July 14. Three days later it warmed its core just enough to be considered a tropical depression, then gained a second wind to become a full-fledged hurricane on July 22 after completing a loop between Bermuda and the Azores.

Three days before pummeling Florida’s Atlantic beaches with storm surge, November 2022’s Hurricane Nicole began as a subtropical storm with a large expanse of winds.

The 2018 hurricane season produced seven storms that were subtropical at least for part of their lifetime, a record number for any season.

Among these was Alberto, which eventually developed into a tropical storm. Its remnants remained intact as far north as Michigan in late May. The seven named storms in the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season that were subtropical at some point in their lifetime, a record number for any year.

“The conditions over the central North Atlantic, where we had a lot of these subtropical systems, were extremely conducive,” Gerry Bell, the lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, told weather.com in 2018.

“We had record-warm ocean temperatures and also record-weak vertical wind shear. That was certainly a player in the overall strength of the hurricane season, as far as numbers go.”

Source: https://www.wunderground.com/article/storms/hurricane/news/2023-09-19-subtropical-storms-explained